A madman and sleeper, seer of a thousand impossible visions, who sees when he imagines. The demon who comes in the first moments of sleep and remains long after waking; the demon he saw, heard, and answers.

Showing posts with label foucault. Show all posts

Showing posts with label foucault. Show all posts

Saturday, March 30, 2024

Saturday, June 20, 2015

About self

We spoke first in terms of the soul and the vessel, then the spirit and the flesh, and then the mind and body. Now we speak in terms of identity and biology.

We spoke first in terms of the soul and the vessel, then the spirit and the flesh, and then the mind and body. Now we speak in terms of identity and biology.

Labels:

anatomical,

Aristotle,

Bruce Jenner,

Caitlyn Jenner,

Descartes,

foucault,

gender,

identity,

myth,

narrative,

news,

philosophy,

race,

Rachel Dolezal,

rhetoric,

self,

selfhood,

sex,

Socrates,

Thomas Aquinas

Friday, July 06, 2012

About secularized religion

As

the Church fell into crisis in the 17th century, an emerging secular

governmentality assumed custodial rights over life and population issues

previously

managed by the Church. With this, the modern State evolved, giving rise

to politics. Like medicine and science, politics grows and takes more

and more things into its body of knowledge, even religion, which itself

is now highly politicized (it has been before

now, but in different ways). The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day

Saints was developed in the context of this politics, and has been

linked to it since the beginning as evident in the religion's history, a

story of battling for political contention.

Taking

this story on a tangent, on June 30 this year, a modest group of Mormons gathered to renounce their membership in the LDS Church using methods

that conflate

the political with the religious: their gathering was personal ceremony

and political protest; they waved a "Declaration of Independence from

Mormonism" and offered letters of resignation, seeking "freedom" as they

gathered at Ensign Peak like Brigham Young

did with his followers in 1847; they sacrificed church-bound

relationships with their community, yearning to receive those same

relationships in return, renewed as social and business ties; their

reasons for quitting included Church teachings that are "made

up", that conflict with science, that conflict with history, that veil

racism and promote intolerance, and that are inconsistent.

Taking

this story on a tangent, on June 30 this year, a modest group of Mormons gathered to renounce their membership in the LDS Church using methods

that conflate

the political with the religious: their gathering was personal ceremony

and political protest; they waved a "Declaration of Independence from

Mormonism" and offered letters of resignation, seeking "freedom" as they

gathered at Ensign Peak like Brigham Young

did with his followers in 1847; they sacrificed church-bound

relationships with their community, yearning to receive those same

relationships in return, renewed as social and business ties; their

reasons for quitting included Church teachings that are "made

up", that conflict with science, that conflict with history, that veil

racism and promote intolerance, and that are inconsistent.

Anyway, this story sort of stuck out like this.

Wednesday, June 13, 2012

About an article indirectly about authors and their texts

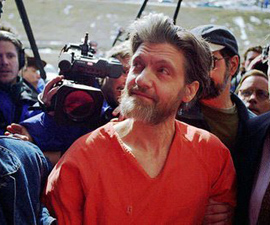

The Chronicle of Higher Education has a sort-of interesting article titled "The Unabomber's Pen Pal" that is about a college professor trying to teach the anti-technology ideas espoused by Ted Kaczynski among others (but especially by him). This professor seeks to remove from the remote Montana cabin and the remote mind of its terrorist author the ideas captured in Kaczynski's manifesto and resituate them in the academy. Apparently it often turns out that exploring the ideas on their own merit takes a backseat to discussing the practicality and ethics of doing so.

Within contemporary literary theory, can the text be removed from its author? How did the author get "into" the text in the first place?

And should he be removed? Is this a special kind of work? A unique case?

Kaczynski lived his ideology and practiced his philosophy. In one sense, by removing the author from the text, the professor is attempting to protect the text, give it viability in the marketplace of ideas. But at the same time, without its author, the text is deprived of the life Kaczynski lived in its manifestation--the life it advocates for, the revolution it endorses: all that is locked away, isolated, imprisoned so as not to threaten its academic life.

To wit, Kaczynski is first locked away so as not to threaten society; then he is locked away a second time so as not to threaten his own ideas. Indeed, the text is freed the moment its author is imprisoned.

"Kaczynski" is now an abstraction of the man who attacked society by sending bombs through the mail while hidden in a remote Montana cabin. When the name is attributed to the text, "Kaczynski" appears in faded print in its margins, and can be found scratched in between the lines, where it adds or invokes a certain character in the work. This character says, Yes, these words are dangerous, these words are of consequence to you and to the establishment. These are fighting words.

This is not to say you can't or shouldn't remove the author from his text (in a sense I'm all for it). It's just that, given the current practice of (critical) literary theory, if you try, you might expect the text to change. After all, the fact that the professor consciously has to remove the author, and that the Chronicle wrote about his trying to do so, shows current theory's unrelenting emphasis and reliance on the author function.

Sunday, October 09, 2011

On Foucault's The Will to Knowledge

In the first volume of The History of Sexuality, The Will To Knowledge, Foucault dissolves the conventional wisdom that says sexuality has been repressed since the Victorian age. He argues instead that it began to flourish in the 18th century through discourse. Conceptually, sexuality came into being then as a social construct that has since permeated our lives. This flourishing began with the rite of confession and from there evolved and spread through the newly powerful institutions of science, medicine, and education. A general example: What was a simple debauchery before came to be identified as a specific perversion--and only one of many possible perversions--that evidenced any number of other sexual issues to be uncovered in the recesses of childhood memory and untangled in the psychiatrist's office and later echoed in the medical texts. Sexuality is a secret we tirelessly mine for truths about ourselves. Foucault doesn't deal in conspiracies. Rather, his are institutional analyses, demystifications of the larger issues and forces at play anytime we and our managers attempt reform and understanding.

This volume--or, at least this translation--feels less inspired than Foucault's earlier works, gifting us with fewer flourishes and specific citations. But the overall concepts are more accessible; for example, the recent history of family medicine and psychiatry are less foreign to casual readers than, say, the innards of the asylum. But my main criticism is this: Madness and Civilization excelled at painting a picture of what madness meant before the modern age took hold of it; The Will To Knowledge, on the other hand, gives us little idea of what sex meant to society prior to the Victorian era. Nevertheless, like any Foucault work, this is to be studied and enjoyed for its originality, insight, thoroughness, style, and potential. And I enjoyed this volume far more than I did the third volume, The Care of the Self.

This volume--or, at least this translation--feels less inspired than Foucault's earlier works, gifting us with fewer flourishes and specific citations. But the overall concepts are more accessible; for example, the recent history of family medicine and psychiatry are less foreign to casual readers than, say, the innards of the asylum. But my main criticism is this: Madness and Civilization excelled at painting a picture of what madness meant before the modern age took hold of it; The Will To Knowledge, on the other hand, gives us little idea of what sex meant to society prior to the Victorian era. Nevertheless, like any Foucault work, this is to be studied and enjoyed for its originality, insight, thoroughness, style, and potential. And I enjoyed this volume far more than I did the third volume, The Care of the Self.

Labels:

book review,

books,

foucault,

normalization,

power,

psychiatry,

repression,

rhetoric,

The History of Sexuality

Wednesday, July 20, 2011

News of their world

At the News of the World phone-hacking hearing, parliamentary members ask questions and Murdoch answers. This discourse is filtered, translated, and expanded by media into a discourse for the public. Where media and the public meet, consumption, demand, answer, and reply intersect.

The hearing is the statement from legitimacy; the pie in the face attempt is the response from illegitimacy, which took shape via the legitimizing power of the hearing. The media covers the illegitimate; this story is but one in an explosion of discourse. The hearing becomes a sideshow, almost irrelevant in an ongoing discussion about the role and standards of media, the particulars of American vs British law and politics, the appropriateness of relationships between media and politicians, corporations and media, and corporations and government.

Then the story expands into oblivion, and all is said at once in silence.

Postmortem: The loudest and most abundant coverage focuses on the personal drama--the relationship between Murdoch and his son, Murdoch and his protege, Murdoch and his wife, the wife and the pie thrower, Cameron and his hired hand. Lost are the victims of the original crime, who, like the important issues of power and corruption, are rendered irrelevant to the spectacle.

The News of the World focused on the sensational. Now the rest of the media follow suit.

The hearing is the statement from legitimacy; the pie in the face attempt is the response from illegitimacy, which took shape via the legitimizing power of the hearing. The media covers the illegitimate; this story is but one in an explosion of discourse. The hearing becomes a sideshow, almost irrelevant in an ongoing discussion about the role and standards of media, the particulars of American vs British law and politics, the appropriateness of relationships between media and politicians, corporations and media, and corporations and government.

Then the story expands into oblivion, and all is said at once in silence.

Postmortem: The loudest and most abundant coverage focuses on the personal drama--the relationship between Murdoch and his son, Murdoch and his protege, Murdoch and his wife, the wife and the pie thrower, Cameron and his hired hand. Lost are the victims of the original crime, who, like the important issues of power and corruption, are rendered irrelevant to the spectacle.

The News of the World focused on the sensational. Now the rest of the media follow suit.

Thursday, June 09, 2011

Shame and Power

News media now push this story about sexually suggestive photos sent via Twitter by New York Congressman Anthony Weiner. A few months ago it was Congressman Christopher Lee emailing shirtless pictures of himself. How are these important? The answer can be found in Foucault.

News media now push this story about sexually suggestive photos sent via Twitter by New York Congressman Anthony Weiner. A few months ago it was Congressman Christopher Lee emailing shirtless pictures of himself. How are these important? The answer can be found in Foucault.These stories share the assumption of scandal--the media's judgement that these actions are inappropriate and deserving of shame and public scrutiny. Media represent power. They are agents of powerful private interests joined at the hip with policy makers who seek control over behavior. Power enforces control, encourages self-control and the policing of peers. Power seeks to regulate sexuality ultimately to ensure the stability of the population (i.e., control population growth, minimize conflicts leading to lawlessness, etc). Weiner and Lee are guilty of expressing their sexuality in unsanctioned ways.

These men--let's pretend they are both guilty--expressed their sexuality in an unobtrusive, non-aggressive way: Electronically. Although the acts are basically harmless and victimless, power aims to extend domination and control over sexuality even as it exists and is practiced in the electronic sphere. Hence, the public shaming.

Labels:

foucault,

government,

media,

politics,

public,

scandal,

The History of Sexuality

Wednesday, May 18, 2011

Popular Stoics

Was surprised and interested to see Foucault indict the Stoics in latter portions of Care of the Self. His analysis, like so much his other work, counters preconceived ideas. I had pictured these philosophers as characters of resignation; and I concluded that this resignation necessarily prevented them from being influential beyond their kin. But not so, according to Foucault; they were enormously influential. And the moral and ethical conclusions they drew from their insistence on understanding nature and being at harmony with the universe profoundly impacted what would become acceptable ways of living and what affinities would become vilified or otherwise expire with the Age.

Labels:

Classical Age,

foucault,

marriage,

philosophy,

power,

Stoicism,

Stoics,

The History of Sexuality

Tuesday, May 17, 2011

When a marriage is legitimate

In Care of the Self, the third volume of The History of Sexuality trilogy, Foucault summarizes the history of marriage. Elite pagans married to form alliances of wealth and power; the poor married for economic practicality (i.e., a poor man might marry a poor woman and they, with their family, could support themselves). These marriages needed only the family's blessing. From there, interests of the State and of the Church took root. Marriages became increasingly social and public.

We have a tendency to look to an institution's origins to inform us on resolving contemporary issues.

We have a tendency to look to an institution's origins to inform us on resolving contemporary issues.

Labels:

civil union,

foucault,

law,

legitimacy,

marriage,

politics,

research,

tradition

Saturday, April 09, 2011

Enlightening Limits

Sizing up the limits of thought proposed during the Enlightenment and urging us to peek at what lies beyond, Michel Foucault poses a very Foucauldian question to himself about such a brief investigation:

In other words, Yes, we run the risk. But I have my ways.

In other words, Yes, we run the risk. But I have my ways.

These quotes come from his brief 1984 piece titled What is the Enlightenment? The question dates from 1784: That year a German paper posed the question and Immanuel Kant answered. In his response to Kant, Foucault proposes that our modern mode of self-reflection took shape then, and he notes the existence and implications of the shaping mechanisms. The Enlightenment, according to Foucault, is essentially an attitude. Several pages in, though, he tosses off this nugget: "Criticism indeed consists of analyzing and reflecting upon limits".

None of his major points hinge on this statement, but I'm really taken with it.

My first thought is that limits make originality possible. Describing a work of art as "original" is often high praise. But something may be original and not necessarily good; agreed? Critics also often assert that a work of art has value when it advances a conversation--conversations about humanity, time, life, sports, religion, whatever. And advancement means moving beyond where we are at present, being presently at the limit, and as far as we have gotten. But a work of art and its critiques may also center on how the work functions within and comments on pre-established limits. Perhaps a work could even impose limits on itself. In these ways a work of art, be it a song, painting, a dance or film, for example, may not necessarily qualify as original.

Criticism of policy may also concern limits. Who is excluded from the policy? How does the policy work? and, How far reaching are its implication?

Criticism indeed consists largely of analyzing and reflecting upon limits.

If we limit ourselves to this type of always partial or local inquiry or test, do we not run the risk of letting ourselves be determined by more general structures of which we may well not be conscious, and over which we have no control?His answer is priceless:

...it is true ... we are always in the position of beginning again.

But that does not mean that no work can be done except in disorder and contingency. The work in question has its generality, its systematicity, its homogeneity, and its stakes.

In other words, Yes, we run the risk. But I have my ways.

In other words, Yes, we run the risk. But I have my ways.These quotes come from his brief 1984 piece titled What is the Enlightenment? The question dates from 1784: That year a German paper posed the question and Immanuel Kant answered. In his response to Kant, Foucault proposes that our modern mode of self-reflection took shape then, and he notes the existence and implications of the shaping mechanisms. The Enlightenment, according to Foucault, is essentially an attitude. Several pages in, though, he tosses off this nugget: "Criticism indeed consists of analyzing and reflecting upon limits".

None of his major points hinge on this statement, but I'm really taken with it.

My first thought is that limits make originality possible. Describing a work of art as "original" is often high praise. But something may be original and not necessarily good; agreed? Critics also often assert that a work of art has value when it advances a conversation--conversations about humanity, time, life, sports, religion, whatever. And advancement means moving beyond where we are at present, being presently at the limit, and as far as we have gotten. But a work of art and its critiques may also center on how the work functions within and comments on pre-established limits. Perhaps a work could even impose limits on itself. In these ways a work of art, be it a song, painting, a dance or film, for example, may not necessarily qualify as original.

Criticism of policy may also concern limits. Who is excluded from the policy? How does the policy work? and, How far reaching are its implication?

Criticism indeed consists largely of analyzing and reflecting upon limits.

Friday, February 25, 2011

Alienation to alienated

When reading Madness & Civilization, know that a lot of people considered normal today would have been diagnosed mad in previous centuries. For example, Foucault spends a great deal of time discussing melancholics, known today as people suffering from depression.

Anyway, finished reading Madness & Civilization. The closing of chapter IX, "The Birth of the Asylum", includes this wonderful sentence--the parentheticals are mine:

He (Freud) did deliver the patient from the existence of the asylum within which his "liberators" had alienated him; but he did not deliver him from what was essential in this existence; he regrouped its (the asylum's) powers, extended them to the maximum by uniting them in the doctor's hands; he created the psychoanalytical situation where, by an inspired short-circuit, alienation becomes disalienating because, in the doctor, it becomes a subject.1

Here, I think Foucault is saying something like this: The structures and practices of the asylum gave doctors moral authority over the mad; doctors objectified the mad in those asylums, thereby alienating them, making them outsiders in the real world of reason. But once patient care fell to psychiatry--most notably with Sigmund Freud--doctors' authority transferred from those structures to the personage of the doctor. The doctor then exercised his authority in the psychiatrist's office. There, the alienation that was, in the asylum, only a side effect of being the anomaly became itself a neurosis to be studied and speculated on.

Pure rad.

His arguments probably don't play well when taken in pieces like this, but one can see how rich the content of his writing is. I could spend three days unpacking this one sentence and still not feel the thing fully fleshed out.

I think the prevailing opinion is that Foucault was not much of a writer. I disagree, although I have only translations to judge by.

1"Madness & Civilization" by Michel Foucault

Labels:

foucault,

Freud,

Madness and Civilization,

medicine,

positivism,

psychiatry,

psychoanalysis,

rhetoric,

science

Sunday, February 20, 2011

Quick Thrill

If I had to choose one by Foucault, I'd take Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison over his more noted Madness and Civilization. I seek the same kind of satisfaction from both, but they are very different in approach and style.

If I had to choose one by Foucault, I'd take Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison over his more noted Madness and Civilization. I seek the same kind of satisfaction from both, but they are very different in approach and style.Now over two-thirds into the book, this week I read chapter VII, "The Great Fear". Heading into the 1800's, Foucault here describes how the public imagination began to see madness as "the strange contradiction of human appetites: the complicity of desire and murder, of cruelty and the longing to suffer, of sovereignty and slavery, insult and humiliation". This conception inspired both fear and attraction to the mad and to the houses in which they dwell.

And still every Halloween people flock to haunted houses in search of a thrill.

Tuesday, February 08, 2011

Moral Charge

"The Great Confinement", the first chapter of Michael Foucault’s Madness and Civilization, traces early reactions to a set of people, including the mad, whose common condition was idleness. His tracing includes a discussion of the role of Europe’s churches; with the aid of the Church, houses of confinement, which frequently doubled as work houses (sources of cheap labor), had a moral charge to assign labor and condemn the idle. Armed with a moral charge, they operated without oversight, without checks on their power, without critical analysis of their judgments because they had the faith of the state. Idleness was a sin, the reasoning went; because of Original Sin men were condemned to labor forever, Earth being no longer a paradise fit to sustain him without aid of his toils.

"The Great Confinement", the first chapter of Michael Foucault’s Madness and Civilization, traces early reactions to a set of people, including the mad, whose common condition was idleness. His tracing includes a discussion of the role of Europe’s churches; with the aid of the Church, houses of confinement, which frequently doubled as work houses (sources of cheap labor), had a moral charge to assign labor and condemn the idle. Armed with a moral charge, they operated without oversight, without checks on their power, without critical analysis of their judgments because they had the faith of the state. Idleness was a sin, the reasoning went; because of Original Sin men were condemned to labor forever, Earth being no longer a paradise fit to sustain him without aid of his toils.Recently I attended church and heard this Gospel:

Mt 5:13-16

Jesus said to his disciples, “You are the salt of the earth. But if salt has lost its strength, how can it be made salty again? It has become useless. It can only be thrown away and people will trample on it.

Jesus said to his disciples, “You are the salt of the earth. But if salt has lost its strength, how can it be made salty again? It has become useless. It can only be thrown away and people will trample on it.

“You are the light of the world. A city built on a mountain cannot be hidden. No one lights a lamp and covers it; instead it is put on a lampstand, where it gives light to everyone in the house. In the same way your light must shine before others, so that they may see the good you do and praise your Father in heaven."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)