Socializing hurts Lars, but through a co-worker he learns of a website that sells life-like sex dolls, so he orders one and, upon her arrival, makes her his girlfriend. To him, she poses no threat. She can be his creation, and from her he creates a saintly Brazilian missionary immigrant named Bianca who, being wheelchair-bound and having a limited understanding of English, is completely dependent upon him.

But soon other townsfolk co-opt his creation, and they make Bianca more dynamic, resourceful, and, eventually, independent. Lars originally used Bianca to approximate intimacy; with her he could relate to the world the way he wanted to be related to--with patience and sensitivity, without possibility of rejection. But suddenly realizing he is no longer Bianca's only connection to this world, thereby feeling rejected, Lars defiantly sets out building connections of his own by going out with a young lady he works with. From there, we put Lars on the road to deliverance from the prison of his inhibitions.

The movie feels sweet, but underneath is a careful power struggle between Lars and the town. Lars' truth is dubbed a delusion, and soon others' truths are being imposed from all sides until Lars, having lost control of his creation, announces that Bianca has died--a final and dramatic act of self empowerment. What is it exactly that either pushes or inspires Lars to change, to conform to the town's normalizing desire for him to be more social?

Sunday, October 30, 2011

Friday, October 28, 2011

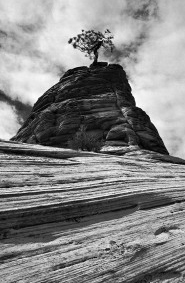

Photos, from some weeks back

Labels:

camera,

dog,

graphics,

neighborhood,

photography,

photos,

pictures,

yard

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

Squashing Dissent

The CNN article "Tear gas used on Occupy protesters in Oakland" quotes police statements released after violent attempts to squash Occupy Wall Street protests. The article does not (1) investigate these statements, (2) include counter statements by protestors or neutral observers, nor does it (3) discuss relevant questions about whether demonstrators needed or acquired permits for their events. This article represents a lot of modern mainstream coverage and is decidedly not journalism. It shows how media outlets function primarily as loudspeakers for establishments, both government and private industry.

OK, maybe every statement can't be checked. That's understandable. But at least say so in the article because a lot of people trust authorities, especially the police, and these people accept official statements as gospel.

My favorite part: The article concludes with this:

OK, maybe every statement can't be checked. That's understandable. But at least say so in the article because a lot of people trust authorities, especially the police, and these people accept official statements as gospel.

My favorite part: The article concludes with this:

Oakland and Atlanta are two of many cities worldwide dealing with the Occupy Wall Street protests, the leaderless movement that started in New York in September.Dealing with?

Labels:

establishment,

mainstream,

media,

news,

occupy wall street,

power,

protest,

violence

Saturday, October 22, 2011

Something on short stories by Carson McCullers

The drifter's wisdom imparted in Carson McCullers' short story "A Tree. A Rock. A Cloud." tells us that love don't come easy. Having first failed at love, this drifter concludes that to be successful he must take baby steps, first feeling love for a tree, a rock, then a cloud--objects seemingly less complicated, less sacred and dangerous than his love's final destination, the woman that got away. He claims his approach is a science. His conclusion indicates that he believes he is not the problem. No, love itself is the problem and, moreover, the beloved is tricky and must be approached with caution. If his conclusion holds true, does this make love impossible for all men? Only the aged can hope for true love. It's a guaranteed tragedy at best.

The drifter's wisdom imparted in Carson McCullers' short story "A Tree. A Rock. A Cloud." tells us that love don't come easy. Having first failed at love, this drifter concludes that to be successful he must take baby steps, first feeling love for a tree, a rock, then a cloud--objects seemingly less complicated, less sacred and dangerous than his love's final destination, the woman that got away. He claims his approach is a science. His conclusion indicates that he believes he is not the problem. No, love itself is the problem and, moreover, the beloved is tricky and must be approached with caution. If his conclusion holds true, does this make love impossible for all men? Only the aged can hope for true love. It's a guaranteed tragedy at best.A similar message is driven home in McCullers "The Ballad of the Sad Cafe". Here she tells of misguided, unrequited love. The three primary characters are defined by a lack of love--either a lack of love given or returned--so much so that they are ultimately victimized by love, turned tragic characters doomed to love an impossibility while drenched in loneliness and soft brutality. The love we can call healthy escapes McCullers' universe.

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

Broken Flowers

In the film "Broken Flowers", Bill Murray plays Don Johnston. I'd guess that Murray's motivation when he plays Don is that he has no motivation at all. The woman leaving him in the film's opening describes Don as an over-the-hill Don Juan, but what's so Don Juan about him, we can't tell. Rather than impassioned and hungry, this aging man is listless and indifferent.

The stoical plot of "Broken Flowers" begins when an anonymous letter informs Don that he has a 19 year-old son who may be looking for him. This revelation leads Don's amateur sleuth neighbor to map out a quest to identify the mother. So Don reluctantly accepts this mission. On his road trip, Don reunites briefly with four women who may have sent the letter. They are his unknowing suspects; Don is their detached inquisitor. These women all respond differently: The first with familiar affection, the next with frigid nervousness, another with distanced suspicion, and the last with outward aggression. None of these encounters leads Don to identify the mother. But once back again in his home town, Don spots a young man loitering first at the bus station, then outside the diner where Don lunches. Don approaches the stranger for an impromptu sit down which ends with Don embarrassing himself and frightening off the apparently wrong young man. It may be that Don never chose to be a confirmed bachelor. It may be that he never chose anything at all. He simply stopped developing but kept being. When the film ends, we can wonder if Don has been stirred again, or we might think this fruitless search has only affirmed his negation. But wait--a strange happening just before the credits only deepens the uncertainty.

Other interpretations: (1) The amateur sleuth neighbor represents the seeker; he is one who searches for Truth. Don is the skeptic, a slightly cynical denier of Truth. But, when Don is faced with the possibility of Truth he reaches out to take hold of it, wanting. But what does it mean that Truth evades him? (2) Another interpretation (my preference): The amateur sleuth neighbor represents the person compelled to exercise power, to subject the world to his gaze and prescribe truths, thereby creating knowledge he uses as he wishes. Don neither wishes to exercise power and refuses to have power exercised on him. When he takes up the quest for power and knowledge, he finds nothing but a stretch of time that is uninterpretable and not to be used for the purposes of meaning, knowledge, and power.

"Broken Flowers" is a good film, if a little flat in its pacing. Bill Murray, of course, awards even this static character with soul.

The stoical plot of "Broken Flowers" begins when an anonymous letter informs Don that he has a 19 year-old son who may be looking for him. This revelation leads Don's amateur sleuth neighbor to map out a quest to identify the mother. So Don reluctantly accepts this mission. On his road trip, Don reunites briefly with four women who may have sent the letter. They are his unknowing suspects; Don is their detached inquisitor. These women all respond differently: The first with familiar affection, the next with frigid nervousness, another with distanced suspicion, and the last with outward aggression. None of these encounters leads Don to identify the mother. But once back again in his home town, Don spots a young man loitering first at the bus station, then outside the diner where Don lunches. Don approaches the stranger for an impromptu sit down which ends with Don embarrassing himself and frightening off the apparently wrong young man. It may be that Don never chose to be a confirmed bachelor. It may be that he never chose anything at all. He simply stopped developing but kept being. When the film ends, we can wonder if Don has been stirred again, or we might think this fruitless search has only affirmed his negation. But wait--a strange happening just before the credits only deepens the uncertainty.

Other interpretations: (1) The amateur sleuth neighbor represents the seeker; he is one who searches for Truth. Don is the skeptic, a slightly cynical denier of Truth. But, when Don is faced with the possibility of Truth he reaches out to take hold of it, wanting. But what does it mean that Truth evades him? (2) Another interpretation (my preference): The amateur sleuth neighbor represents the person compelled to exercise power, to subject the world to his gaze and prescribe truths, thereby creating knowledge he uses as he wishes. Don neither wishes to exercise power and refuses to have power exercised on him. When he takes up the quest for power and knowledge, he finds nothing but a stretch of time that is uninterpretable and not to be used for the purposes of meaning, knowledge, and power.

"Broken Flowers" is a good film, if a little flat in its pacing. Bill Murray, of course, awards even this static character with soul.

Labels:

acting,

age,

art,

Bill Murray,

Broken Flowers,

character,

criticism,

film,

happiness,

loneliness,

love,

marriage,

romance,

Stoicism

Sunday, October 16, 2011

Current narrative on Occupy Wallstreet

The media narrative on Occupy Wall Street says the participants have no clearly defined unifying goal or policy objective. By contrast we're shown the Tea Party who want smaller government and less taxes. Nevermind that "smaller government" and "less taxes" are amazingly broad demands that, if actually instituted, would result in changes that the Tea Party would not support, including cuts to the military, cuts to US farm and oil subsidies, and cuts to Social Security and Medicare (presumably, once unknowing senior Tea Party members are made aware these are government-run programs, some would change their mind).

Occupy Wall Street's thematic conceptual equivalent to "smaller government" and "less taxes" is probably "inequality" because this key word holds much meaning for the protestors: Inequality of wealth distribution (the poor get poorer and the rich get mega-rich), inequality of bailout-giving (big banks get 'em, homeowners and college loanees don't), inequality of criminal prosecutions (white collar crimes are often ignored, crimes of the poor cause prisons to spill over), and so on.

If the narrative is true that Occupy Wall Street lacks a cohesive, meaningful message, then it is equally true of the Tea Party. In fact, as the Tea Party grew in number, its aims became even more diverse, including Obama citizenship-deniers, health care reform opponents, social conservatives, fiscal conservatives, veterans, seniors, libertarians, the rich and the poor. Yet they were celebrated in the media for allegedly lacking leadership and being a true-blue grass roots movement. The same benefit of the doubt is denied Occupy Wall Street.

Occupy Wall Street's thematic conceptual equivalent to "smaller government" and "less taxes" is probably "inequality" because this key word holds much meaning for the protestors: Inequality of wealth distribution (the poor get poorer and the rich get mega-rich), inequality of bailout-giving (big banks get 'em, homeowners and college loanees don't), inequality of criminal prosecutions (white collar crimes are often ignored, crimes of the poor cause prisons to spill over), and so on.

If the narrative is true that Occupy Wall Street lacks a cohesive, meaningful message, then it is equally true of the Tea Party. In fact, as the Tea Party grew in number, its aims became even more diverse, including Obama citizenship-deniers, health care reform opponents, social conservatives, fiscal conservatives, veterans, seniors, libertarians, the rich and the poor. Yet they were celebrated in the media for allegedly lacking leadership and being a true-blue grass roots movement. The same benefit of the doubt is denied Occupy Wall Street.

Labels:

civil rights,

foreign policy,

inequality,

media,

movement,

narrative,

news,

occupy wall street,

party,

politics,

protest,

tea party

Friday, October 14, 2011

Bias in prisoner swap story

Mainstream outlets cover the Israeli-Palestinian prisoner swap from the Israeli perspective (i.e., "Israeli Solder to be Released") while others and foreign outlets go either way. In this case (pictured at right), only Al Jazeera takes an angle on the Palestinian prisoners.

Incidentally, the ratio of prisoners being freed (1000 Palestinians to 1 Israeli) is interesting because it lends itself to either of two diametrically opposed conclusions: (1) 1000 to 1? How many warmongering Palestinians are there?, or (2) 1000 to 1? How could the Israelis imprison so many Palestinians?

Incidentally, the ratio of prisoners being freed (1000 Palestinians to 1 Israeli) is interesting because it lends itself to either of two diametrically opposed conclusions: (1) 1000 to 1? How many warmongering Palestinians are there?, or (2) 1000 to 1? How could the Israelis imprison so many Palestinians?

Labels:

conflict,

interpretation,

Israel,

media,

middle east,

narrative,

news,

Palestine,

peace,

rhetoric

Sunday, October 09, 2011

On Foucault's The Will to Knowledge

In the first volume of The History of Sexuality, The Will To Knowledge, Foucault dissolves the conventional wisdom that says sexuality has been repressed since the Victorian age. He argues instead that it began to flourish in the 18th century through discourse. Conceptually, sexuality came into being then as a social construct that has since permeated our lives. This flourishing began with the rite of confession and from there evolved and spread through the newly powerful institutions of science, medicine, and education. A general example: What was a simple debauchery before came to be identified as a specific perversion--and only one of many possible perversions--that evidenced any number of other sexual issues to be uncovered in the recesses of childhood memory and untangled in the psychiatrist's office and later echoed in the medical texts. Sexuality is a secret we tirelessly mine for truths about ourselves. Foucault doesn't deal in conspiracies. Rather, his are institutional analyses, demystifications of the larger issues and forces at play anytime we and our managers attempt reform and understanding.

This volume--or, at least this translation--feels less inspired than Foucault's earlier works, gifting us with fewer flourishes and specific citations. But the overall concepts are more accessible; for example, the recent history of family medicine and psychiatry are less foreign to casual readers than, say, the innards of the asylum. But my main criticism is this: Madness and Civilization excelled at painting a picture of what madness meant before the modern age took hold of it; The Will To Knowledge, on the other hand, gives us little idea of what sex meant to society prior to the Victorian era. Nevertheless, like any Foucault work, this is to be studied and enjoyed for its originality, insight, thoroughness, style, and potential. And I enjoyed this volume far more than I did the third volume, The Care of the Self.

This volume--or, at least this translation--feels less inspired than Foucault's earlier works, gifting us with fewer flourishes and specific citations. But the overall concepts are more accessible; for example, the recent history of family medicine and psychiatry are less foreign to casual readers than, say, the innards of the asylum. But my main criticism is this: Madness and Civilization excelled at painting a picture of what madness meant before the modern age took hold of it; The Will To Knowledge, on the other hand, gives us little idea of what sex meant to society prior to the Victorian era. Nevertheless, like any Foucault work, this is to be studied and enjoyed for its originality, insight, thoroughness, style, and potential. And I enjoyed this volume far more than I did the third volume, The Care of the Self.

Labels:

book review,

books,

foucault,

normalization,

power,

psychiatry,

repression,

rhetoric,

The History of Sexuality

Friday, October 07, 2011

Celebrity among the titans of industry

Thursday on NPR staffer Guy Raz and The Wall Street Journal tech columnist Walter Mossberg discussed Steve Jobs' legacy. Raz asked, "Is there anybody living today that is remotely his peer, anywhere close to his genius?" Mossberg answers, "Well, I am a technology writer, and I, you know, there may be people in other industries and other walks of life, but certainly in the technology business and in American business in general, I actually don't think there is anyone. You know, if you look at the headline of the print Wall Street Journal this morning, it just simply says Steven Paul Jobs, 1955-2011, over six columns. And we've been talking here on our - in our staff trying to think of who other than the president of the United States would merit a headline upon his death in The Wall Street Journal of that magnitude? And we just can't think of anybody." The media's recent deification of Jobs is reflexive, and especially so in this case, with a WSJ columnist gauging significance through the actions of his own media outlet.

Step outside this circle of media attention begetting celebrity begetting media attention and we might argue that, Of course Jobs is a historical giant--he's the reason we all have personal computers, making this the Information Age and all that entails. But this is also the result of media simplifying a narrative and thereby making a myth of creation. Jobs did not work alone; his innovations had impact to be sure, but the man and his ideas are not the sole seed of the Modern Age.

Could an artist ever receive such accolades from the media? Not likely, if The Wall Street Journal has any say. Validation and recognition is saved for the rich and powerful.

Step outside this circle of media attention begetting celebrity begetting media attention and we might argue that, Of course Jobs is a historical giant--he's the reason we all have personal computers, making this the Information Age and all that entails. But this is also the result of media simplifying a narrative and thereby making a myth of creation. Jobs did not work alone; his innovations had impact to be sure, but the man and his ideas are not the sole seed of the Modern Age.

Could an artist ever receive such accolades from the media? Not likely, if The Wall Street Journal has any say. Validation and recognition is saved for the rich and powerful.

Labels:

art,

business,

celebrity,

media,

power,

rhetoric,

technology,

validation

Wednesday, October 05, 2011

NPR goes wildly awry

Under the headline An Update On The 'Three Cups Of Tea' Lawsuit, NPR reports news of a class action lawsuit filed by donors to Greg Mortenson's charity as named in his now defamed book, Three Cups of Tea. Then the reporters, led by Melissa Block, call the lawsuit frivolous. Melissa Block begins pushing the frivolous angle when she asks court reporter Gewn Florio, "Gwen, when you talk to lawyers there, are there people who think that there is a reasonable basis for this suit to go forward? It does seem like they're launching pretty novel claims here. Or do they assume that it will be dismissed?"

Under the headline An Update On The 'Three Cups Of Tea' Lawsuit, NPR reports news of a class action lawsuit filed by donors to Greg Mortenson's charity as named in his now defamed book, Three Cups of Tea. Then the reporters, led by Melissa Block, call the lawsuit frivolous. Melissa Block begins pushing the frivolous angle when she asks court reporter Gewn Florio, "Gwen, when you talk to lawyers there, are there people who think that there is a reasonable basis for this suit to go forward? It does seem like they're launching pretty novel claims here. Or do they assume that it will be dismissed?"Why would the case be summarily dismissed? Mortenson set up a fraudulent charity and solicited funds for that charity via marketing efforts built on his book and media appearances. School children donated to this guy's cause; why should they and the rest of his donors not have recourse to the law? Melissa Block keeps pushing the frivolous angle, asking, "Is anybody there in Montana saying this is just a case of lawsuits gone wildly awry, that this should not be settled in a court? That if they felt bad about buying the book or giving their money that's one thing, but this is not the basis of a class-action lawsuit?" To which Florio concedes with disinterest, "Sure, I think people say that, yeah exactly, this is not the way to settle it. That he's been discredited, people will no longer buy the book, things sort of play out in the marketplace." Mortenson is already rich--the marketplace was the vehicle for his fraud; the courts are where justice is supposed to be done, so let them decide the merits of the case.

Sunday, October 02, 2011

Jack Goes Boating

Philip Seymour Hoffman's performance as Jack in Jack Goes Boating reminds me of Wilson, his character in Love Liza. Jack is a stunted man just awakening to possibility, and the movie ends with him starting a new phase of life through a relationship with a woman who understands him; Wilson had a good relationship and professional life, but the movie begins when that phase abruptly ends, his wife having just committed suicide, wounding him indefinitely. Jack is getting up, whereas Wilson is falling, perhaps landing at the movie's end. These films resemble snapshots but unfold narratives every bit as epic as that of Star Wars or The Lord of the Rings.

Although Jack is painfully quiet, Hoffman broadcasts Jack's inhibitions and insecurity by prescribing a subdued nervousness to the character's bearing. But we also witness Jack's sweet, gentle spirit when he listens repeatedly to his favorite song, the limited soundtrack he's assigned to his compact existence. Philip Seymour Hoffman is the best actor we have.

Although Jack is painfully quiet, Hoffman broadcasts Jack's inhibitions and insecurity by prescribing a subdued nervousness to the character's bearing. But we also witness Jack's sweet, gentle spirit when he listens repeatedly to his favorite song, the limited soundtrack he's assigned to his compact existence. Philip Seymour Hoffman is the best actor we have.

Friday, September 30, 2011

Giving and taking rights

Women in Saudi Arabia will be able to vote in that country's next election. Meanwhile, in America states are adding new voting barriers for the poor.

Wednesday, September 28, 2011

Going out on a high note

Article conclusions in The New York Times often mislead the audience. Two common types of conclusions that do readers a disservice are (1) the happy ending and ( 2) giving an opinion the last word.

First, the happy ending can negate a serious discussion. We saw an example of this yesterday in the article "Deep Recession Sharply Altered U.S. Jobless Map". The article focuses on high unemployment rates in the American South and West. Of course, this discussion omits mention of employment and business trends that preceded the recession--the decline of manufacturing jobs due to off-shoring, for example. Nevertheless, after discussing high unemployment, the article ends with this:

This "things are looking up" conclusion wipes out everything preceding it.

This "things are looking up" conclusion wipes out everything preceding it.

The second kind of ending is the conclusion that gives one opinion the last word. Giving an opinion the last word legitimizes that opinion, and that opinion becomes the reader's takeaway. We see an example of this today in the article "Wealthy, Influential, Leaning Republican and Pushing a Christie Bid for President". This piece says that a group of wealthy, elite business and financial leaders are pushing New Jersey Republican Governor Chris Christie to run for president. The article hints that these elites favor Christie not solely for his charisma, but also for his anti-union stance and record of fiscal conservatism. Of course, that these policies might damage the middle and working classes and the poor goes unstated, and absolutely no voice is given to critics of Mr. Christie. This glowing opinion of the NJ Governor gets the last word:

First, the happy ending can negate a serious discussion. We saw an example of this yesterday in the article "Deep Recession Sharply Altered U.S. Jobless Map". The article focuses on high unemployment rates in the American South and West. Of course, this discussion omits mention of employment and business trends that preceded the recession--the decline of manufacturing jobs due to off-shoring, for example. Nevertheless, after discussing high unemployment, the article ends with this:

But Mr. Kaglic said that the recent return of manufacturing jobs was giving him hope, and that one reason for the high unemployment rate was that more people were now seeking work.

“I would look at it as our dreams are delayed,” he said, “rather than our dreams being denied.”

This "things are looking up" conclusion wipes out everything preceding it.

This "things are looking up" conclusion wipes out everything preceding it.The second kind of ending is the conclusion that gives one opinion the last word. Giving an opinion the last word legitimizes that opinion, and that opinion becomes the reader's takeaway. We see an example of this today in the article "Wealthy, Influential, Leaning Republican and Pushing a Christie Bid for President". This piece says that a group of wealthy, elite business and financial leaders are pushing New Jersey Republican Governor Chris Christie to run for president. The article hints that these elites favor Christie not solely for his charisma, but also for his anti-union stance and record of fiscal conservatism. Of course, that these policies might damage the middle and working classes and the poor goes unstated, and absolutely no voice is given to critics of Mr. Christie. This glowing opinion of the NJ Governor gets the last word:

“I had Christie to our board meeting the April after he took office, and he knocked their socks off,” said Kathryn Wylde, president of the Partnership for New York City, a business group with a gold-plated roster of prominent Democratic and Republican moneymen. “And ever since, there’s been nothing but enthusiasm for him. He’s considered smart, courageous, a straight talker, kind of an antipolitician.”So is this what the reader is to conclude about Chris Christie? What about his record? What affect might his policies have on the 99% of people who aren't pushing a Christie bid? What will Christie do for them? Lots of people want Kucinich or some other Progressive to run, but this fact gets no coverage. This Christie article shows without saying that money buys office, our system is corrupt.

Labels:

class,

corruption,

media,

news,

newspapers,

politics,

power,

rhetoric,

the new york times

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Lady Gaga's Little Monsters

The fantasy Lady Gaga sells her fans is one of homogeneous fame ("You’re a superstar, no matter who you are!”). Their real life, which actually is authentic, is replaced by an inauthentic fantasy. Lady Gaga offers her Little Monsters only the denial of self-authorship.

The fantasy Lady Gaga sells her fans is one of homogeneous fame ("You’re a superstar, no matter who you are!”). Their real life, which actually is authentic, is replaced by an inauthentic fantasy. Lady Gaga offers her Little Monsters only the denial of self-authorship.Serving the artist's commercial interest, these fans find comfort, support, and acceptance when together they assume the label Little Monsters. They believe that their self-identification as freaks and outsiders embraces their outsider status, the counterpoint to a mainstream composed of their more popular, better looking peers. But rather than creating a social alternative, they have simply recreated an in-group within the larger mainstream which inadvertently pushes new fashions, concepts of coolness, and other cornerstones of capitalism. In doing so they are even more integral to the system they feel alienated from. They welcome and modify trends, furthering the cycle of need and acceptance.

Labels:

capitalism,

celebrity,

counter culture,

criticism,

culture,

economy,

fame,

idols,

mainstream,

self-image

Sunday, September 25, 2011

Poem by Rainer Maria Rilke

A poem--can't swear to the translation or line breaks:

A poem--can't swear to the translation or line breaks:For Hans Carossa

-by Rainer Maria Rilke

Losing too is still ours; and even forgetting

still has a shape in the kingdom of transformation.

When something's let go of, it circles; and though we are

rarely the center

of the circle, it draws around us its unbroken, marvelous

curve.

Labels:

art,

criticism,

interpretation,

poem,

poetry,

Rainer Maria Rilke,

Rilke

Friday, September 23, 2011

Palestinian statehood

Spiegel gave a compelling and fairly even account of the implications and stakes surrounding the leadership of Palestine's UN bid for statehood.

Labels:

civil union,

EU,

Europe,

Israel,

media,

middle east,

Obama,

Palestine,

politics,

United Nations

A thought on the film No Country for Old Men

In No Country for Old Men, the killer Anton deals in consequences. He is the harbinger of the heartless world, a bringer of death who does not decide who lives and dies. To his mind, what you're doing and where you find yourself traces back to either chance or to some choice you made. He has no patience for ambiguity; fortunes hinge on the flip of a coin and once you call it, results are sure to follow. In this story, Anton's primary target is the hunter Llewellyn Moss.

Moss, now finding himself the prey, resists the inevitable, plotting his escape as best he can given what little wiggle room he has. He acts, and when acted upon, he counters. If ultimately the outcome falls to chance, he will throw his weight on the scale and make sure his chance is the fighting kind.

Sheriff Bell reflects on both men: Permanence and change, fate and self-determination weigh on his mind. He sees men like Anton as evidence the light is fading from this world. After fate claims Moss and untethered chance visits Anton, Bell is left awake in a world that's always been dark and cold, dreaming of the succession of humble men like him who can't do much about it.

Moss, now finding himself the prey, resists the inevitable, plotting his escape as best he can given what little wiggle room he has. He acts, and when acted upon, he counters. If ultimately the outcome falls to chance, he will throw his weight on the scale and make sure his chance is the fighting kind.

Sheriff Bell reflects on both men: Permanence and change, fate and self-determination weigh on his mind. He sees men like Anton as evidence the light is fading from this world. After fate claims Moss and untethered chance visits Anton, Bell is left awake in a world that's always been dark and cold, dreaming of the succession of humble men like him who can't do much about it.

Tuesday, September 20, 2011

On Percy Walker's The Last Gentleman

I had a longish review of The Last Gentleman but lost it through Google. So here's the shortened version:

I had a longish review of The Last Gentleman but lost it through Google. So here's the shortened version:Williston Bibb Barret was lost. With much help he discovered that his troubles belonged to man's condition and not to him alone. He found a future when he accepted one--in this case, the orthodox life of marriage, kids, church, and so on. Not as good as The Moviegoer but still very good.

Sunday, September 18, 2011

Friday, September 16, 2011

Jon Stewart's rhetorical situation

I like this quasi-profile of John Stewart because the author approaches his subject from various angles, posing provocative questions and then offering answers, alternately recognizing strengths while attacking some well-argued weaknesses. The primary criticisms leveled at Stewart are that (1) he takes himself too seriously and (2) he unknowlingly plays the redeemer, criticizing the establishment from a safe place while making himself invulnerable to counter-criticism by repeatedly denying his power--this "redeemer" characterization of Stewart refers to America's "need for redeemers to rise out of its ranks". Its a great read but I argue that the author puts too much emphasis on Stewart the individual and not enough on the larger rhetorical situation.

I agree that his modesty borders on false, but when Stewart denies his power I interpret this as his assessment not so much of himself but of his rhetorical situation: His audience consists of young, self-imagined dissidents and slackers who ultimately don't mobilize well as a group. Stewart can't mobilize them the way Beck can appear to mobilize his audience--a block of voters already energized thanks to a dedicated media and powerful political machine. Despite mainstream media's claims to the contrary, the Tea Party is not a "state of mind" or unaffiliated multiplicity of citizenry; they are an easily identified demographic with shared values and an agenda. By comparison, Progressives can stand for almost anything--gay marriage, worker's rights, the environment, anti-globalization, minority achievement, tax policy, gun control, prison reform, entitlement improvements, education, peace, and so on--and getting them to the polls as individuals is challenging enough. Stewart's power lies solely in his popularity as a smart Liberal media critic, a face appearing not on reputable stages like CNN or even MSNBC, but on Comedy Central for a few minutes a night, four nights a week during part of the year. The matter is not that Stewart won't be a force for change; it's that he can't be.

The author implies that Stewart is a coward because he stands for nothing; he only satirizes while acting as the Liberal conscience. But then the piece ends with Stewart dreaming up a network based on media reform. Isn't that standing for something? (If it is true.) If Stewart does nothing more than The Daily Show the rest of his life, then No, he isn't politically useful to Progressives. He merely provides a venue for people who think popular news is a joke.

But as a media attraction (as opposed to a political force), Stewart does have power. So I don't follow the criticism that Stewart takes himself too seriously. So what if he does? The author's cited examples include his behavior during appearances on Charlie Rose, Rachel Maddow, or on various FOX programs. Look, when Stewart is given a serious platform such as a guest spot on Charlie Rose, he acts like a guest on Charlie Rose. He takes advantage and shows another other side of himself. As for switching between Stewart the TV personality and Stewart the man, entertainment has a long history of performers trying to reach through the wall separating performer from audience in an attempt to connect. When the run of a show ends, like when Conan had to leave his show or when Carson retired from his, the man opts for sincerity as sincerity is called for.

In the peripheral sits an interesting issue: What to make of Stephen Colbert? Right now, neither man has a cause or larger vision with which to rally voters. But among his other achievements, Colbert formed a super PAC and gave a scathing, high-profile performance at the White House Correspondents Dinner. In criticizing Stewart, is the author alternately congratulating Colbert? Is Colbert still funny?

I agree that his modesty borders on false, but when Stewart denies his power I interpret this as his assessment not so much of himself but of his rhetorical situation: His audience consists of young, self-imagined dissidents and slackers who ultimately don't mobilize well as a group. Stewart can't mobilize them the way Beck can appear to mobilize his audience--a block of voters already energized thanks to a dedicated media and powerful political machine. Despite mainstream media's claims to the contrary, the Tea Party is not a "state of mind" or unaffiliated multiplicity of citizenry; they are an easily identified demographic with shared values and an agenda. By comparison, Progressives can stand for almost anything--gay marriage, worker's rights, the environment, anti-globalization, minority achievement, tax policy, gun control, prison reform, entitlement improvements, education, peace, and so on--and getting them to the polls as individuals is challenging enough. Stewart's power lies solely in his popularity as a smart Liberal media critic, a face appearing not on reputable stages like CNN or even MSNBC, but on Comedy Central for a few minutes a night, four nights a week during part of the year. The matter is not that Stewart won't be a force for change; it's that he can't be.

The author implies that Stewart is a coward because he stands for nothing; he only satirizes while acting as the Liberal conscience. But then the piece ends with Stewart dreaming up a network based on media reform. Isn't that standing for something? (If it is true.) If Stewart does nothing more than The Daily Show the rest of his life, then No, he isn't politically useful to Progressives. He merely provides a venue for people who think popular news is a joke.

But as a media attraction (as opposed to a political force), Stewart does have power. So I don't follow the criticism that Stewart takes himself too seriously. So what if he does? The author's cited examples include his behavior during appearances on Charlie Rose, Rachel Maddow, or on various FOX programs. Look, when Stewart is given a serious platform such as a guest spot on Charlie Rose, he acts like a guest on Charlie Rose. He takes advantage and shows another other side of himself. As for switching between Stewart the TV personality and Stewart the man, entertainment has a long history of performers trying to reach through the wall separating performer from audience in an attempt to connect. When the run of a show ends, like when Conan had to leave his show or when Carson retired from his, the man opts for sincerity as sincerity is called for.

In the peripheral sits an interesting issue: What to make of Stephen Colbert? Right now, neither man has a cause or larger vision with which to rally voters. But among his other achievements, Colbert formed a super PAC and gave a scathing, high-profile performance at the White House Correspondents Dinner. In criticizing Stewart, is the author alternately congratulating Colbert? Is Colbert still funny?

Labels:

celebrity,

comedy,

criticism,

media,

politics,

popularity,

power,

profile,

rhetoric,

rhetorical situation

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)